Our Beginnings

In 1998, recognizing changes in society, the wishes of its members, and its expanded role in the community, the Association changed its name; it is now the Developmental Disabilities Association.

“You have great hopes and dreams for your children; you think they’re going to be a little bit better than yourself… and when Bobby was born, I did too. When we learned he was retarded, it was a great shock to us… but I felt very responsible for this little entity I had brought into the world.” These are the words of the late Mrs. Leola Purdy, whose second son, Bobby, was born with Down syndrome and suffered further brain damage from a forceps delivery.

Bobby was born in Vancouver in the late 1930’s. Mrs. Purdy visited several doctors, who all told her that her son was “severely retarded,” that there was no hope that he could live anything close to a normal life and that he would probably never even learn to walk. She was told that she should send Bobby to the Woodlands School for the Retarded, an institution located in New Westminster. But as she said, “…it just didn’t seem right to take a little fellow like this out of his family circle and put him in an institution.” She had hoped that when Bobby reached school age, he would at least be admitted to the Vancouver School Board’s special classes for slow learners. What she found out, however, was that the schools accepted only “educable” children, and under their definition, that didn’t include Bobby.

It was a common story in those days. Parents of developmentally disabled children faced frustration and despair, isolation from others like themselves and were cut off from their circle of friends. They sometimes felt ashamed and believed their problems were unique.

A psychologist with the School Board suggested that Mrs. Purdy contact other parents to bring them together to help each other. At first, Mrs. Purdy was hesitant:

“I’d never been a joiner, a club person. I didn’t even know about Robert’s Rules of Order… But it was haunting me. I knew it was not right, that these were human beings who should have the opportunity to be trained to the limits of their ability.”

And so, one night in January of 1952, Mrs. Purdy brought together twelve parents who had a school-aged child who had been rejected by the public school system. All had faith that their children could benefit greatly from education and training. After that first meeting, a provisional board was appointed, headed by the late Bob Moore, and Leola Purdy was named President of the Board. Press notices were put into the local newspapers and soon more parents came forward. In April, the newly formed association was officially registered under the Societies Act, named the Association for the Advancement of Retarded Children. It was the very first association for the developmentally disabled in British Columbia.

Education

The Association’s first years were dedicated to developing educational services. Within a month of the association’s incorporation, the first daytraining class for children had been organized at Knox United Church. Parents took their children to the church, which for some meant a long walk or streetcar ride. Association members took care of all the details of running a school, including curriculum, supplies, books and insurance. They also took turns teaching classes and driving.

The first paid teacher arrived at the school with experience training disabled children in England. Hired in the fall of 1952, she was paid $10 a month.

Children with special needs were referred to the association’s school by education, health and social welfare agencies. Parents also came forward on their own to enroll their little ones. Finally, there was another option besides Woodlands Institution. By the fall of 1952, the class was moved to St. Michael’s Anglican Church, and soon there were nearly 30 children enrolled.

Families constantly struggled against public opinions, either conscious or unconscious, that people with developmental disabilities were second-class citizens, so advocacy became an important part of the association’s mission.

In 1954, the Provincial Government gave the association a grant to appointan Executive Director. The Board chose their founder, Mrs. Purdy. The salary was $250 a month, but it freed her to intensify the effort to gain support for the association’s services and recognition for the rights of people with developmental disabilities. Her advocacy paid off immediately.

By 1955 there were more than 50 pupils at St. Michael’s, but parents grew dissatisfied with the idea of educating their children in makeshift church premises. To solve the problem, a four-room building at Sir Sandford Fleming Elementary School was renovated and opened with 80 students. It was meant only as a temporary solution, however, and planning immediately started for a new school to be administered by the school board.

In 1956, the Public Schools Act was amended to allow school boards to fund schools for mentally disabled students operated by associations at the same per diem rate that it cost to teach typical children.

It was an important political move, since the government formally acknowledged its responsibility to educate children with developmental disabilities.

In 1959, the government amended legislation to allow school boards to provide accommodation for special needs schools and gave them the right to establish and operate their own classes for students with disabilities. Furthermore, the higher costs of educating individuals with developmental disabilities were recognized and funding was increased to 150% of the per diem rate for typical students.

Oakridge School opened on May 12, 1961, with 113 pupils. It was Canada’s first school for students with developmental disabilities built and administered under a public school board. The activities of the association continued to introduce citizens to the needs and potential of people with developmental disabilities, generating community acceptance. By the end of the 1980s, Oakridge School was closed and all children with special needs were placed in typical classrooms, alongside other children their age.

Infant Development Program

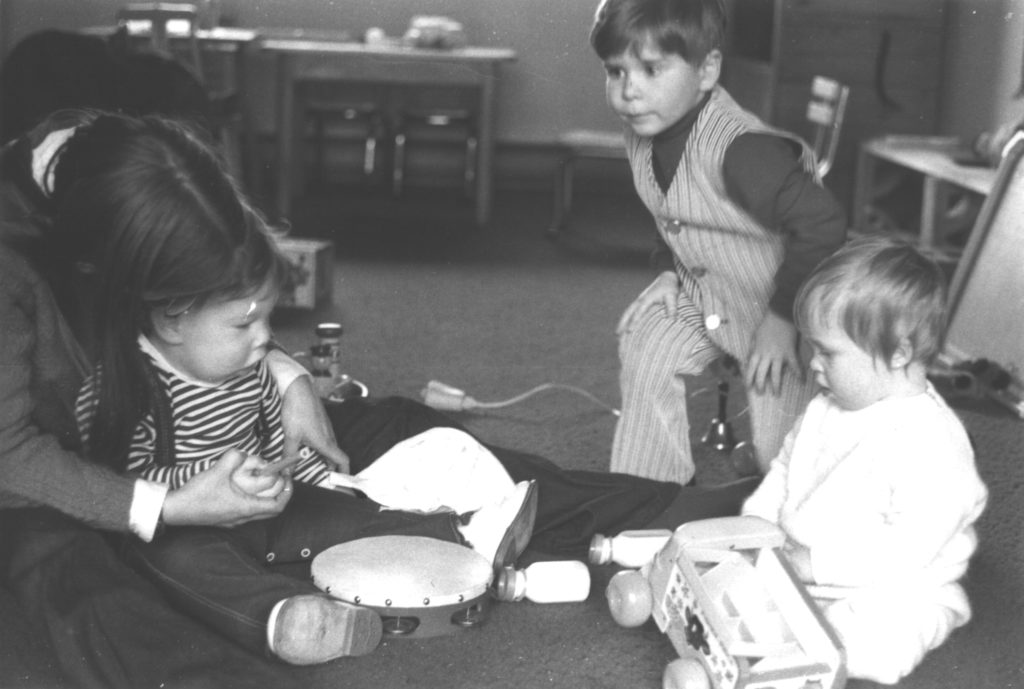

Research that started in the 1950s demonstrated the benefits of specialized training for children with developmental disabilities. To put this research to the test, the association set up groups to teach parents what to expect of their special needs infant or toddler. The initial study groups culminated in the creation of the Infant Development Program (IDP). The premise, supported by scientific research, was that movement and sensory stimulation in a child’s earliest months could lead to significant and lasting gains in development.

The program was spearheaded by a group of parents of young children with developmental disabilities who convinced the association to support a pilot project, starting in the summer of 1972. With the help of volunteers, the program developed rapidly.

As part of the program, trained professionals visited families in their homes and worked with groups, showing how simple equipment – a balance board, a partly inflated beach ball or an infant swing – could be used to stimulate development and at the same time provide a happy play experience for children and their parents.

The provincial government was so impressed with the program that the government decided to make Infant Development services available to other regions in 1973. Dana Brynelsen worked for the association but spent her time promoting academic research and infant development throughout British Columbia, and later, all the world.

Preschool

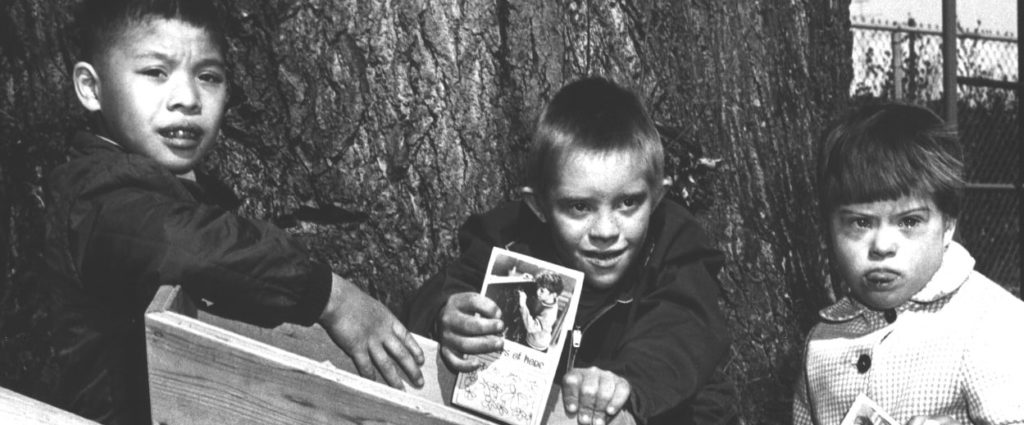

An important collaboration with the University of British Columbia started in 1966 when the Association opened a threeyear pilot preschool. Two years later, the British Columbia Mental Retardation Institute was formed to train professionals such as psychologists, teachers, psychiatrists and doctors to work with children with developmental disabilities, a first in British Columbia.

In 1974 the UBC preschool moved into the Bob Berwick Centre situated on UBC grounds. Accommodating 32 preschoolers, the new facility was built with funds raised by the Variety Club.

The association’s preschools continued to grow in number and size, demonstrating the need for early special needs education but by the mid-1980s, research showed greater developmental progress could be achieved through integration. In September of 1986, the first group of typical three-year-old children began attending Richmond’s preschool two days per week to make it one of the few partially integrated child centres in the province at that time.

With the success of early integration in preschools, parents became less willing to accept segregated education programs. As a direct result of strong parental lobbying, major changes took place in child care, public schools and college programs to the extent that all children participated in an integrated setting for at least part of their education.

Employment

In the early days of the association, parents sometimes doubted their children could ever do productive work, but as the first generation of children in the school program became young adults, their families wanted them to participate in some sort of vocational training.

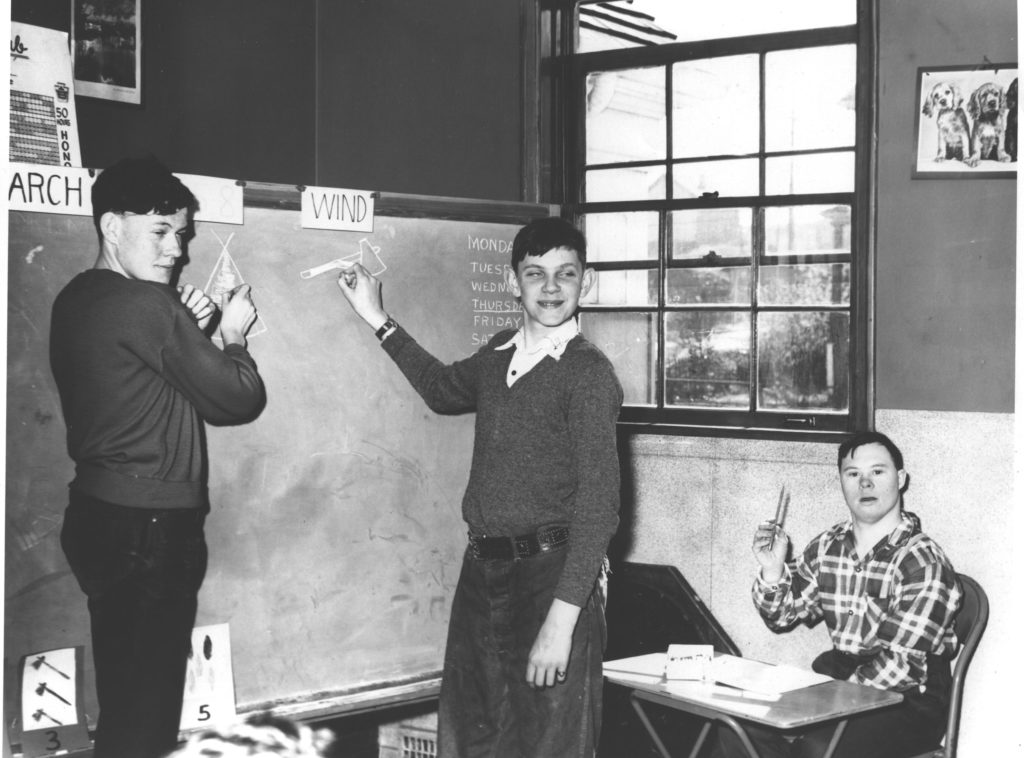

In 1959, a pilot workshop program started in a classroom provided by the school board. The emphasis was on simple woodworking and crafts, but little attempt was made to solicit contracts. Participants made end tables or bookcases, primarily for their own use and satisfaction.

In 1962, the school board donated a building to the association but it had to be moved to a property on Marine Drive which the association had purchased. The new workshop facility was given the name VARCO, the Vancouver Association for Retarded Children’s Occupational Centre.

VARCO canvassed local businesses and was rewarded with a trickle of small-scale assembly and packaging work. The number of participants grew, so in 1967 a $75,000 expansion made room for a total of 100 trainees.

By 1970, VARCO was again too small so the association decided to open a second workshop on the east side of Vancouver. The Clark Drive building was purchased in 1972 with the help of the provincial government. In only two years, the facilities were brimming again. A third workshop was soon opened in Richmond.

By 1977, two more workshops were developed with over 200 trainees. The work was varied and included crafts, packaging, collating and woodworking.

From 1981 to 1982 the association established Hero’s Food Service program and a Hero’s restaurant. The food service training program and business enterprise productively involved eighteen workers with developmental disabilities. Twenty people learned skills such as dishwashing, salad preparation, and people-related skills involved with catering, banquets, and front counter customer service. Many participants in the program moved on to successful employment in restaurants. Unfortunately, due to a poor location, lack of customers and loss of revenue, the association withdrew from operating Hero’s restaurant in 1999.

In 1984, an innovative new approach for employing people with developmental disabilities was implemented with funding from Canada Works. The idea was to take selected trainees out of the workshops and place them into productive and profitable community jobs. The project became a real alternative for adults wanting to work in regular jobs and earn normal wages. The typical industries in which these workers found jobs were warehousing, food services, janitorial and electronic assembly.

As a response to amendments in the Employment Standards Act, by the end of 1999 the Association had closed its ‘sheltered workshop’ programs and replaced them all with new, innovative options that paid trainees minimum wage (or better) and/or offered training in areas selected by the individuals served.

Starworks Packing and Assembly resulted from this re-organization in 2000. Designed as a self-sustaining business where previous ‘clients’ became employees in a venture that paid for itself through fulfillment of work contracts, individuals now had the opportunity to work for full wages and learn the responsibilities of taking home a significantly larger paycheque. Although the goal was to hire 19 people with developmental disabilities, Starworks quite quickly employed 40!

Fundraising & Public Relations

Fundraising and public relations became major priorities for the association beginning in 1987. Public relations informed and provided education to the public, helping to reduce the negative misconceptions people still carried about people with developmental disabilities. Fundraising also became necessary to meet expanding community need and reduced government funding.

In 1998, the Vancouver Richmond Association for the Mentally Handicapped became the Developmental Disabilities Association (DDA) and the Developmental Disabilities Foundation (DDF) was formed to separate fundraising from government revenue. An important source of funds for the association came from a purchasing agreement with Value Village in 1980. The association collected donations of clothing and furnishings and sold them to Value Village, a major thrift retailer in North America, for a profit. In 1998, the Developmental Disabilities Trust (DDT) was also established to oversee

the direction of the business. Over the next few years, business operations grew substantially.

Although the business operated a fleet of trucks to pick up recyclables at the curbside, a Bin program was initiated in 2002 so people could donate anytime, anywhere. 300 donation bins were placed around the Lower Mainland, serviced by a fleet of 10 trucks and a “Donation Station”, a large warehouse where people could bring donations of household items and clothing.

The association went through much growth and many structural changes in the late 1990s. Demands for services continued to increase while government funding decreased and the DDT explored new methods to increase profits.

In 2000, the association’s head office was moved from Vancouver to Richmond to reduce expenses and co-locate the clothing recycling business with DDA administration.

A new mission statement for the association was created in 2001:

“We enable people with developmental disabilities to achieve their full potential.”

The Developmental Disabilities Association: Today

Today, the Developmental Disabilities Association is a community living agency that provides over 50 community-based programs and services to children and adults with developmental disabilities and their families in Vancouver and Richmond.

We create extended networks of support, invest in an individual’s potential, and strive for an inclusive and safe community. Over 1,800 individuals and their families in the Vancouver and Richmond area are supported by DDA every year.

Since 1952, the Association has maintained the philosophy of providing high quality services for people with developmental disabilities to enable them to reach their full potential.

DDA also continues to advocate in the community and with governments to provide opportunities for people with developmental disabilities to live, work and be truly included everywhere.

DDA is also an innovative association – we have introduced new technologies to help people become more independent and support adults to become safer in the community. The Association also partners with Canadian universities and the technology industry to develop assistive robots and new technologies that can positively impact the future of all people with developmental disabilities.

DDA enjoys a host of community partnerships with companies, government and non-government agencies to fulfill our mission. Our work “takes a village” and we are grateful to everyone who helps individuals with developmental disabilities achieve their full potential. DDA is also thankful for the thousands, of staff who have worked with us over so many years to transform dreams into realities.